Pari Singh

Handbook to Iterative Systems Engineering

Volume I — Introduction & Culture

How we do systems engineering has changed. In this volume we talk deeply about engineering culture, what agile and iterative looks like in practice and why all this matters so much right now.

Chapter 1 — State of Hardware Engineering: RIP Waterfall. Hello Iterative

For the first time since the Apollo missions, there’s been a fundamental change in systems engineering—How we do systems engineering has changed.

The teams and leaders that “get it” and operate in the new way will win. They will design hardware at a scale and speed never before seen. Those who don’t get it will start strong, see issues late in their program, and eventually die out. It’s as simple as that.

For the first time since the Apollo missions, there’s been a fundamental change in systems engineering—How we do systems engineering has changed.

The teams and leaders that “get it” and operate in the new way will win. They will design hardware at a scale and speed never before seen. Those who don’t get it will start strong, see issues late in their program, and eventually die out. It’s as simple as that.

The traditional waterfall model is breaking. People will tell you, “Of course it’s not, for complex and safety-critical systems.” We disagree.

We believe iterative systems engineering has been demonstrated to be (a) Faster, (b) Cheaper and (c) Safer than traditional waterfall projects.

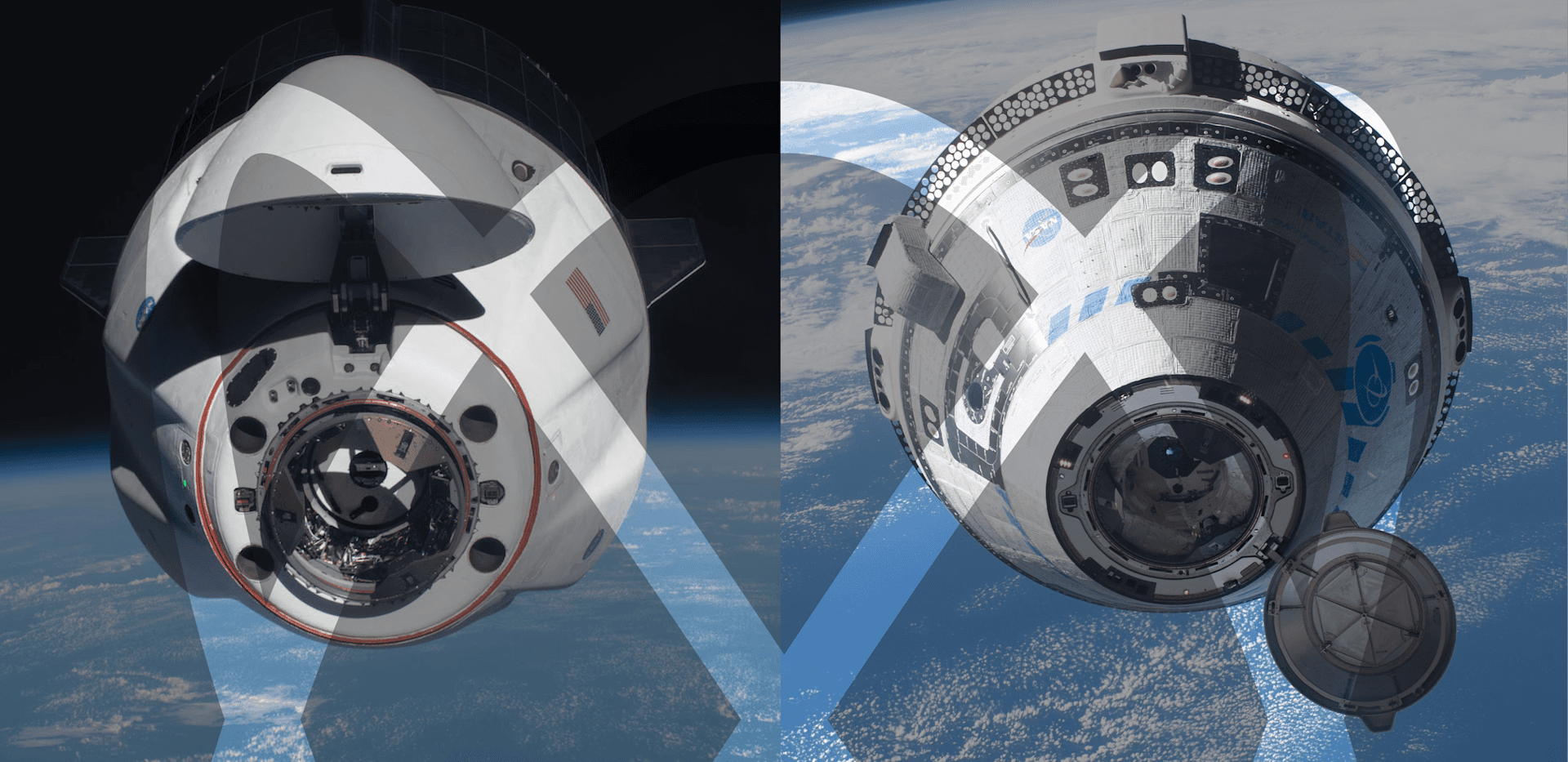

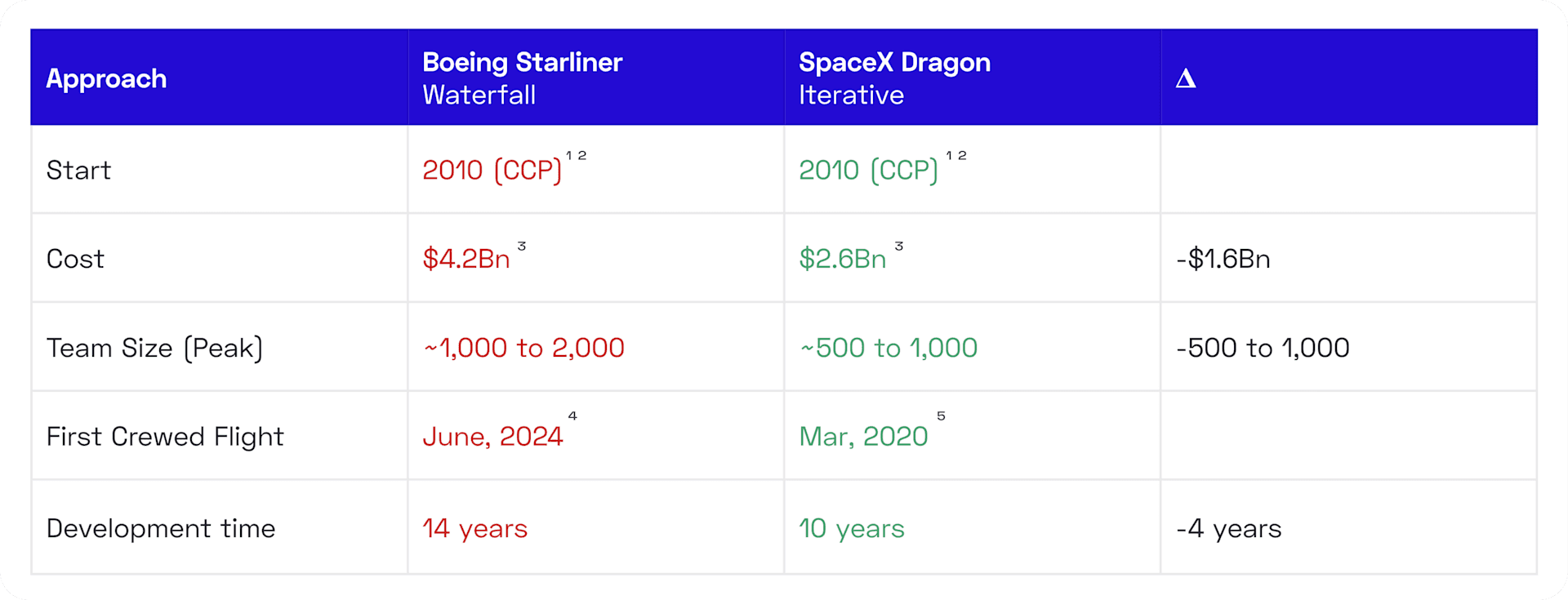

Case Study: SpaceX vs Boeing

The clearest example of this is SpaceX vs Boeing on the COTS (Commercial Orbital Transportation Services) commercial space program.

It is a perfect A/B test of Agile/Iterative vs. Waterfall.

If we assume the same quality and safety levels (they’re not), this is the difference in the numbers:

¹ CCP program starts with $1.3Bn to be awarded for commercial companies to begin taxiing crew to the International Space Station (ISS)—Sep 30, 2010 [Source]

² CCPDev 2 awarded for SpaceX and Boeing for development of Crew Dragon and Starliner—Apr 25, 2011 [Source]

³ NASA awards $4.2 billion (Boeing) and $2.6 billion (SpaceX)—Sep 16, 2014 [Source]

⁴ Boeing Crew Flight Test Heads to Space Station—Jun 5, 2024 [Source]

⁵ First Crewed Test Flight of SpaceX Crew Dragon—May 30, 2020 [Source]

What is Iterative/Agile Systems Engineering?

This book will help you understand the iterative mindset. Before you do, you must be able to intuit it.

The Parable—Quantity is the Fastest Route to Quality

There is a famous parable in the book Art and Fear that goes like this:

This is the parable that teams and leaders must internalize. Once you do, you will be unstoppable.

A ceramics teacher announced on opening day that he was dividing the class into two groups. All those on the left side of the studio, he said, would be graded solely on the quantity of work they produced, all those on the right solely on its quality. His procedure was simple: on the final day of class, he would bring in his bathroom scales and weigh the work of the “quantity” group: fifty pounds of pots rated an “A,” forty pounds a “B,” and so on.

Those being graded on “quality,” however, needed to produce only one pot—albeit a perfect one—to get an “A.”

Well, grading time came and a curious fact emerged: the works of highest quality were all produced by the group being graded for quantity. It seems that while the “quantity” group was busily churning out piles of work—and learning from their mistakes—the “quality” group had sat theorizing about perfection, and in the end had little more to show for their efforts than grandiose theories and a pile of dead clay.

Iterative Systems Engineering Summarized

Iterative is optimized for speed and progress.

It is continuous and cyclic. If done right, you will repeat the process over and over, improving quality each time. It requires a mix of top-down and bottom-up working.

The motto of Iterative Systems Engineering is “Learn by doing”.

If you imagine a car engine, iterative is less efficient but much more reliable. Because it’s not finely tuned, it handles change better. When things change, it has buffer and flexibility. It is inherently stable for high-change projects.

Why is Iterative Faster?

If waterfall is built to be more efficient, why do we see waterfall projects continuously ship with major delays and much higher costs than iterative counterparts?

The answer is that in modern programs, things change quickly. Waterfall is very bad at dealing with change. When change happens, it requires you to effectively restart.

In modern programs, waterfall is theoretically cheaper but requires you to hit restart on billion-dollar projects again and again.

Waterfall's Fatal Flaw is Change and Adaptability

Waterfall is optimized for efficiency.

Although cheaper and faster on paper, this is a hypothetical idea that never turns to reality. Delays and billion-dollar overruns plague waterfall programs.

The major issues of waterfall come down to change. It assumes that requirements will stay the same. It assumes your early design assumptions are correct and will carry through the project. It only catches integration issues at the end of the project, which means frequent delays.

The motto of the traditional Waterfall model is “Design it right the first time”.

It’s built for a world where we’ve done the thing 100 times, know exactly every step, and will be correct. The idea is that if we think through the process well enough, we can integrate once and things should magically fit together.

"Waterfall is about doing what the requirements told you to do. Agile is about having an impact on customers. If the requirements are wrong, change them."

Quinn Scripter

VP Engineering, Planet

It is linear and sequential. If done right, you will only do anything once. It is mostly driven top-down.

We will demonstrate that although this is technically correct on paper, it no longer holds.

Continuing on the car engine example, waterfall is perfectly tuned. This makes it inherently unstable; a tiny grain of sand in the gears will cause the whole thing to collapse.

Why Now? Change and Complexity is Accelerating

So is iterative a choice? Or will it be the new de facto way of doing complex systems engineering?

We believe iterative/agile will be the new de facto way of doing engineering for all major new programs. Why?

There are four main drivers:

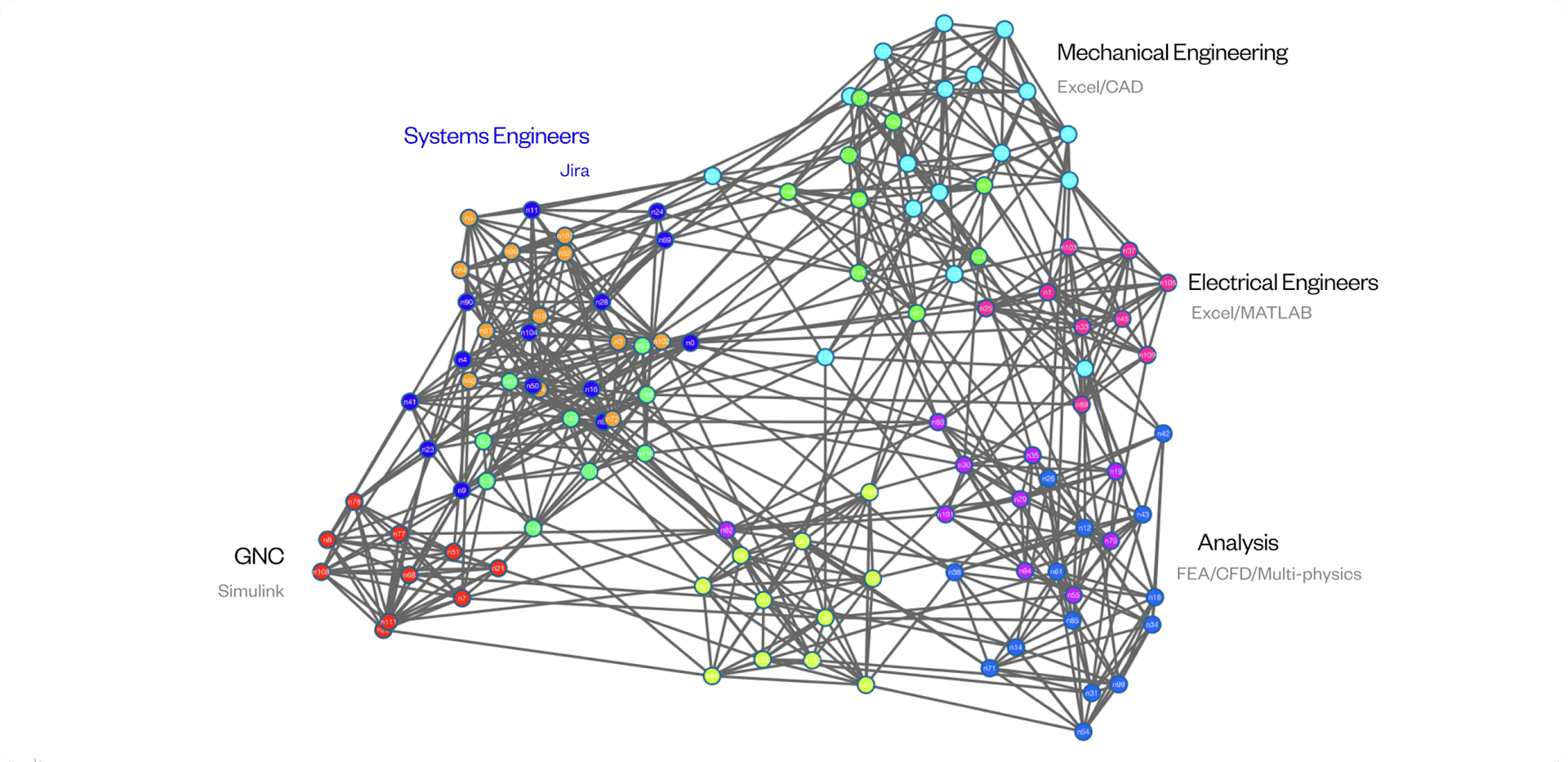

Change Type 1: Systems Complexity

💡 The driving market change behind iterative is an exponential increase in systems complexity.

Over time, three major things have occurred:

Domain complexity: A rise in domain complexity (e.g., thermal systems, propulsion systems) makes them more complex.

Cross-functional complexity: Our systems are much more interdependent and interconnected than before.

Software complexity (and autonomy): Computers now sit at the heart of most modern products, controlling safety-critical systems, whether it’s cars, nuclear reactors, medical devices, or rockets. Most are controlled by computers. Fly-by-wire is now the norm. Autonomy increases this issue 1000x.

Every extra node in this graph means exponentially more work and an exponential slowdown.

A small change in one place will invalidate changes everywhere.

The more important point is that on projects so complex, there’s effectively no way for you to be right on all your early-stage design/requirements assumptions. There will be lots of change.

Change Type 2: Customer/Market Requirements Change

"Ship frequently to test your validation hypothesis. Waterfall focuses on "did it work" vs. Agile's "did it impact the customer?""

Quinn Scripter

VP Engineering, Planet

Then you add a critical final factor: the customer.

From my personal experiences in the defence industry, engineers HATE changing requirements.

They see it as the customer not properly understanding their own needs.

Let’s assume a radical idea for a second: the customer is right.

It’s not so much that the customer’s requirements are changing, but the market landscape is changing and companies need to keep up. War is a landscape that is changing quickly, so is energy. When the enemy utilizes a new weapon, the customer’s needs change. Space is the same, as are nuclear, EVs, and medical fields. The markets evolve, so needs evolve. This has always been true.

The difference is that the customer/market is now asking for things faster. They need to move quickly with the best guess on their requirements. Those requirements will change over months, not decades, as markets evolve.

"Markets and customer needs change. Investors want to see you're adaptable to market needs, which means iteration speed. If you can't iterate fast, there's a risk the market will change, and you won't keep up. Planet needs to see impact fast, so the 10-year NASA approach can't work.

Quinn Scripter

VP Engineering, Planet

It’s no longer good enough to say, “You asked for this 10 years ago” so here it is. Teams that serve yesterday’s ideas will go out of business as market and customer needs change.

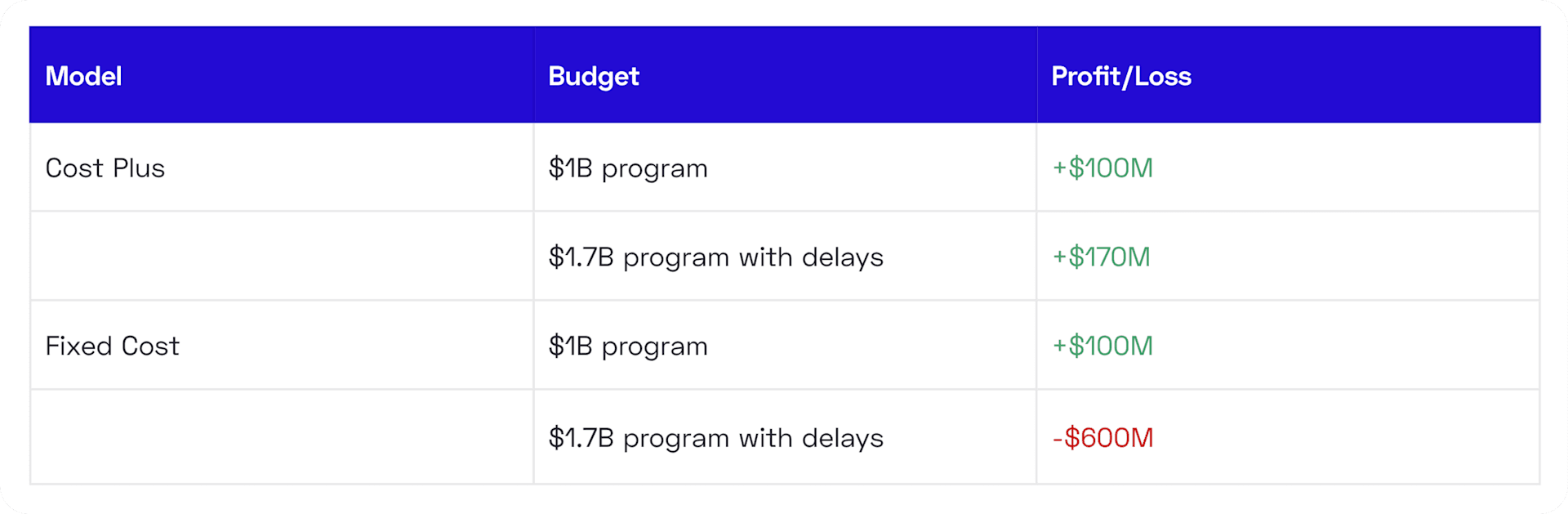

Change Type 3: Cost Plus → Fixed Cost Model

The final case for iterative is that the fundamental business model for our industry is changing.

Before, the cost-plus model meant that the more inefficient we were, the more we earned. Now it’s the opposite.

As a very simple example:

We are (finally) incentivized not to mindlessly hire large teams who sit in analysis paralysis, but to deliver value.

We realize that the single biggest cost is the salaries of 1000+ people. Therefore, time is money.

Suddenly we start looking at things differently:

How can we move faster?

Are there interim steps/products we can release along the way that make us money?

How do we make sure we’re building the right thing?

Change Type 4: Green Teams

This one is overlooked.

If you’re designing the world’s first ultra-heavy launch vehicle, the world’s first fusion reactor, or a new type of product that’s never been done before, you need iterative.

This is because, like Type 1, your early-stage assumptions will likely not be correct and require modification. There’s no way you can know as no one has done it before.

Let’s say you’re not designing a world’s first—you’re still probably designing this type of reactor/car/rocket for the first time.

Let’s say all of that isn’t true—well, your team is still designing this iteration for the first time.

Waterfall is great if you’ve done this exact iteration 100 times and know every step and substep inside and out, but if anything changes at all, you’re better off with iterative.

We need to be less certain and more open to ambiguity. More open to the idea that our knowledge is assumptions, and those assumptions may change.

Iterative vs Agile

Roughly the same idea. The true word for this new era of engineering is probably something like “adaptable,” but it reads less well.

Agility is the ability to respond to change.

Iterative is MVP, V2, V3.

If you have one, you probably have the other. They are not the exact same idea but in this book, we’ll refer to them interchangeably.

So that’s the backbone of why this is important. Let’s now dive into the specifics.

Chapter 2 — Systems Engineering Culture at SpaceX

SpaceX approaches systems engineering (SE) differently from most in the industry. Interestingly, if you ask a SpaceX engineer about systems engineers, they'll say they don't have any. If you ask their opinion on systems engineering, they'll use a four-letter word.

What's odd is that SpaceX is the world's largest and most advanced systems engineering organization—they just don't realize it.

Many modern companies in space, aerospace, nuclear, and automotive sectors are trying to copy SpaceX's approach, but they don't fully understand it. We've distilled their core approach into five tactics you can use to enhance systems engineering in your team.

Here are eight ways to improve your systems engineering.

1. Making decisions right vs making right decisions

At SpaceX, decisions are made immediately, by one person, as soon as they come up. They’re made by the person closest to the problem, not the most senior. This is Responsibility—SpaceX runs on it.

So what happens when something goes wrong? Easy. Just make another decision. Immediately. If that goes wrong? Make another. If that fails, you’re probably in the wrong business

Get to the heart of what you're trying to learn or demonstrate in this iteration. If you build a machine that churns out iterations, you'll know that if you miss it on this one, you'll get it on the next.

Pari Singh

CEO, Flow Engineering

Move the mental model from "What’s the perfect solution?" to "Shots on goal." Play darts, not chess.

2. Every Engineer is a Systems Engineer

The core idea that makes SpaceX work is ownership.

SpaceX doesn't have traditional systems engineers. They believe that in a modern engineering team, the traditional systems-engineer-as-a-document-person, isn’t useful. Engineers themselves need to own things like requirements.

At SpaceX, engineers are called RE's, or responsible engineers.

A responsible engineer is like a blend of an engineer (like a mechanical engineer), a systems engineer, and a chief engineer.

"What’s changed is that systems engineering isn’t just one team in a corner office anymore—it’s a role where everyone needs to be involved in systems thinking, especially in complex products."

Pari Singh

CEO, Flow Engineering

NASA has a different systems engineering philosophy. NASA JPL is fundamentally a systems integrator, with large functional teams that divide tasks. For instance, at JPL, the GNC team only tackles GNC problems, assuming that the actual vehicle is someone else's responsibility.

This is the opposite to what is needed in a fast, modern systems environment.

SpaceX realized that those who own the design must also own the requirements and challenge them. Sometimes, a small adjustment in requirements of one team can make another team's job 100x easier, making it cheaper and potentially saving months on the timeline.

The core realisation here is that either everyone is a systems engineer, or no one is. Responsible engineers design the global system first, and their local sub-system second.

To be able to do this, you need to build a culture of ownership, responsibility and systems mindedness. How do you start this? Simple. Have engineers take ownership of requirements they design against and empower them to question those requirements if they see ways to expedite the program.

Building a culture of responsibility is everything. Tools help, but it starts with people.

Ian Jimenez

VP Engineering, ABL

Moreover, having the systems team own requirements separate from the team doing the work creates a disconnect.

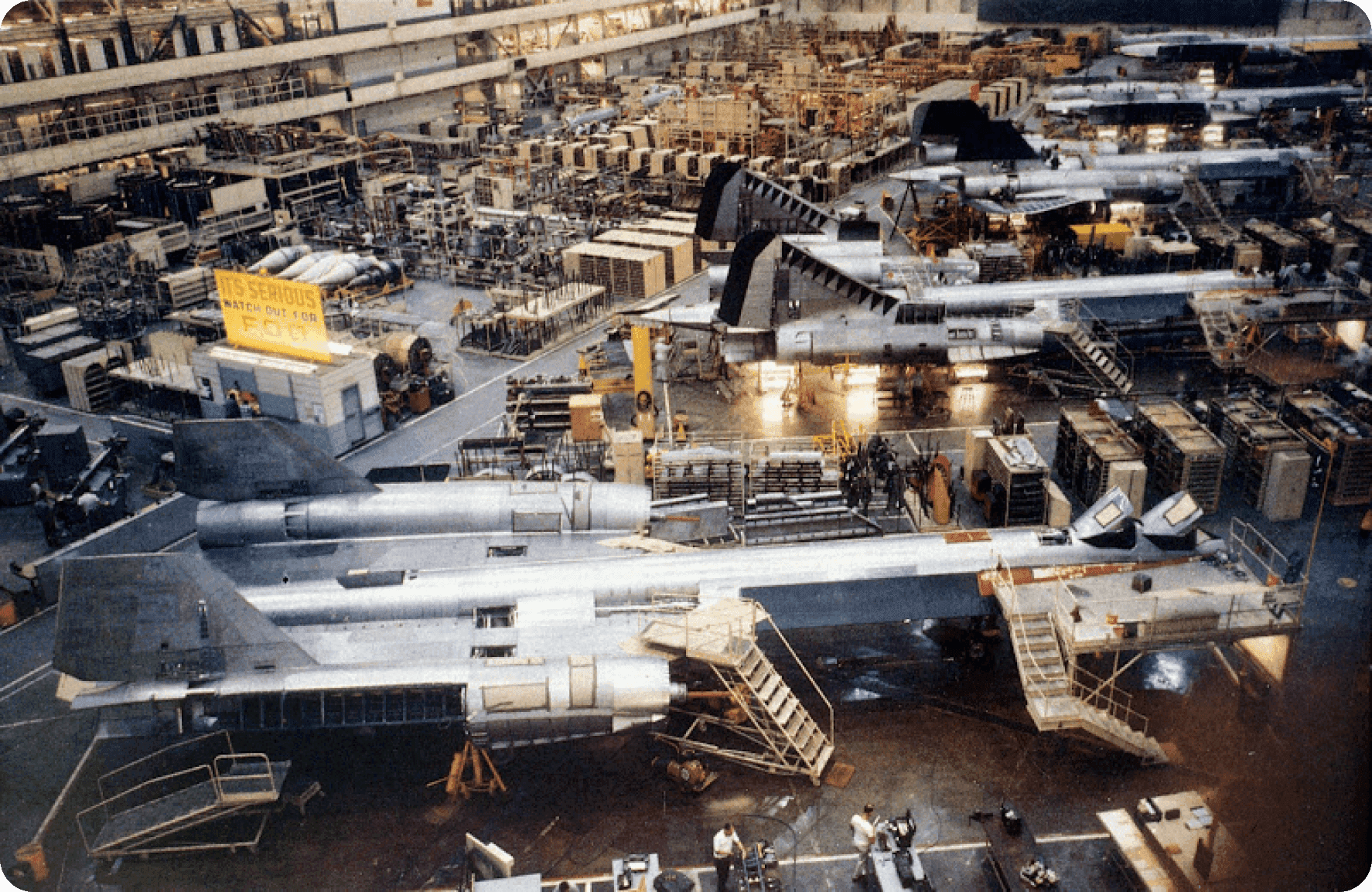

3. The Secret Recipe—Cross-Functional Engineering Collaboration

SpaceX understands that every problem is a systems problem.

The SR71 Blackbird - one of the greatest feats of systems engineering of all time

Rocket reusability is a prime example: Who owns reusability? GNC? Yes, but you also need to consider turning a rocket around in orbit and bringing it back to Earth. So, you add GNC and perhaps some small thrusters for booster rotation. Then, you realize you need to reignite the engines for landing, involving the Merlin/Raptor engine teams. However, fuel sits at the top of tanks during reentry, not at the bottom, so you need a tank team to pressurize the tanks. Then, you need to add grid fins for control... and so on.

In order to solve really hard problems, every engineer needs to be a systems engineer first and a domain engineer second. They must be willing to make sacrifices in their area for the overall benefit of the system. While this sounds simple, it's incredibly challenging to put into practice.

Build "reps" with your team on the full lifecycle to build it into the culture. Everyone from engineering to manufacturing to test needs to learn together. The best way to do that is to ship something smaller faster. Hermeus started with a rocket-powered go-kart and are now building humanity's fastest airplanes.

Skyler Shuford

COO, Hermeus

4. Systems Engineers Are Called “Design Reliability Engineers”

In a world of RE's, what becomes of the systems engineer?

They move up a notch. Instead of focusing solely on documents, they facilitate rapid information flow. They transition from writing requirements to guiding responsible engineers in their approach, spotting cross-functional hurdles, and foreseeing second and third order impacts that local engineers might miss.

What makes for a good requirement? Are we connecting it to the right functions across teams? Is information propagating efficiently, or are we dropping the ball?

Systems engineers shift from execution monkeys to the leaders and advocates of the systems mindset and process, aiding faster and more reliable synchronization among cross-functional teams.

Job description of design reliability/criteria engineer

SpaceX dislikes the traditional role of systems engineers, so they've renamed them as design reliability engineers. This reflects their true task: ensuring the safe, dependable integration of systems.

In this new model, the finest systems engineers are often former REs who have moved up or individuals deeply empathetic to the RE role.

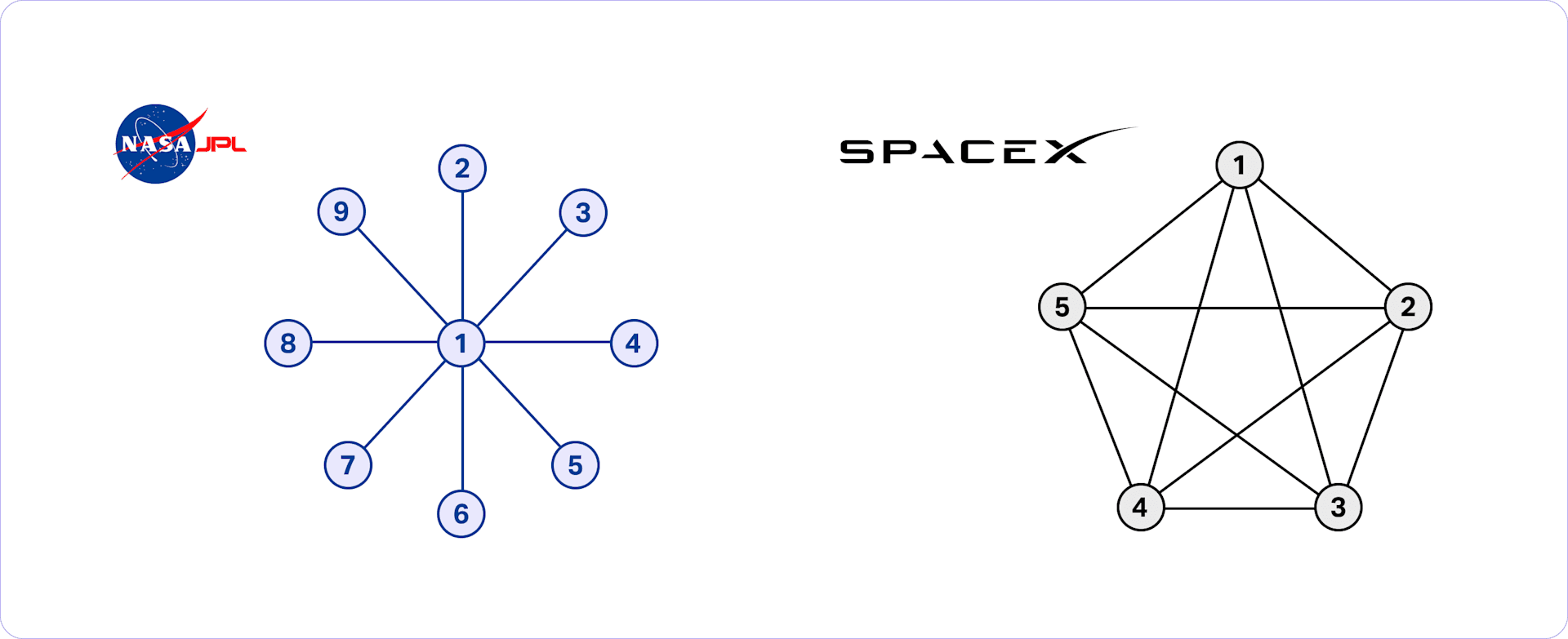

5. Networked vs Centralized Systems Collaboration

Achieving this requires a fundamentally different collaboration model.

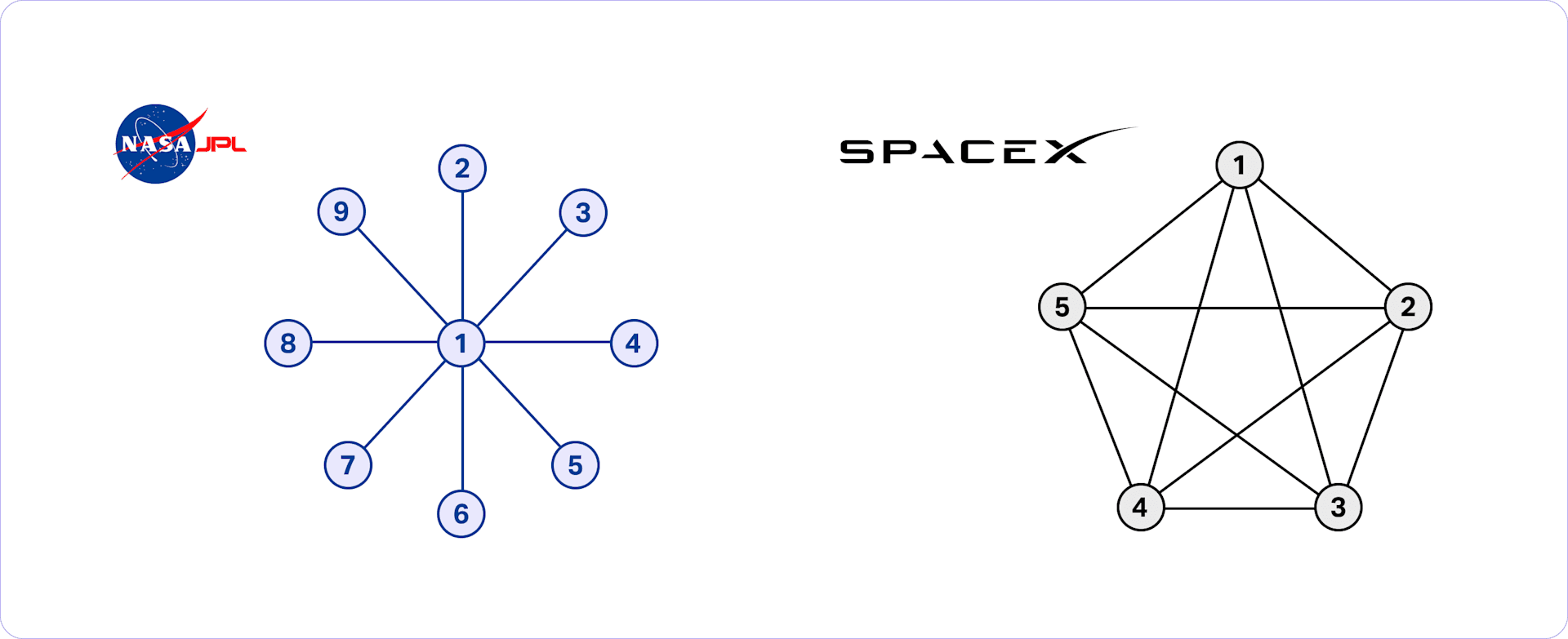

A great way of visualising the difference between the old JPL approach vs. the new agile approach is to think about a star vs a network. A great systems team is networked not siloed.

To visualize, compare the old JPL approach to the new agile approach: a star vs. a network. A robust systems team is networked, not siloed.

Contrasting the bad “siloed” way where everyone feeds into a central systems engineering team good against the networked way where engineers talk to engineers and propagate changes to requirements.

In the old star model, all system information flows into a central team and then out to engineers. Teams only think about what they’re on the hook for and not the overall mission. This leads to creating hostility across the groups.

Why the networked model is superior:

System owners (REs) can negotiate requirements directly.

Every engineer understands their role in making the entire system function, not just their part.

Changes propagate faster across the system.

In the new network model, information flows constantly. However, this can lead to chaos, which is why you need stage gates and to draw a line on what goes in this iteration vs the next iteration.

Systems engineers shouldn't merely shuttle information; they should facilitate cross-functional discussions when issues arise.

But beware the pitfalls:

REs need control over lower-level requirements.

Teams must adapt to late-stage changes, with rework likely.

Constant change is the norm.

So why do it at all?

It’s faster to get something wrong quickly 3 times and then right the 4th, than it is to get it perfectly right the first time, and take 20 years to do so. This is the core principle of the iterative/agile approach.

It's faster to make a 3" telescope, then a 6" telescope, than to make a 6" telescope straight away. Learn by doing, not by thinking.

Skyler Shuford

COO, Hermeus

6. Urgency—just start building without hard requirements

Cost is driven by time, not materials. SpaceX probably spends $250M+ a month (made-up number), or $8M+ a day. If you wait for full requirements, you’ll spend $500M without shipping or learning anything.

Think of time as a requirement, not a resource. Then force as much scope into that time as you can, not the other way around. The biggest cost in development is time (large team * salaries).

Skyler Shuford

COO, Hermeus

What are the real requirements for Starship? Cost per kg, launch rate, full reusability, Mars. Reaffirm the top-line requirements and trust engineers with the rest. Requirements will come, likely after designing starts. Expect mistakes, and call it learning.

Huge congratulations to all our friends at SpaceX. Thanks for leading the way.

7. Rename Internal Requirements to Design Criteria

Requirements are the most important interface across engineering teams.

If you're designing rocket engines, you need to deliver thrust and achieve a certain Delta-V. To accomplish this, you rely on input requirements from other teams, such as the propulsion team supplying fuel/oxidizer at a specific rate, and you have output requirements like thrust affecting various parts of the organization. Changes in thrust impact multiple teams (trajectory, GNC, Structures, etc.), turning into requirements for them.

At SpaceX, external-facing hard constraints requiring full V&V are still called requirements, used in interactions with entities like NASA/DoD.

However, lower-level internal requirements aren't labeled as requirements; they're termed design criteria.

Why the different terminology? It's all about psychology.

Let's face it, "requirements" can carry negative connotations among engineers. The term implies rigid constraints that are seen as commandments that can’t be scrutinised or changed.

For example: Suppose you're given a requirement that your control system must weigh less than 100kg. You can achieve this within 12 months. Alternatively, you could propose increasing the weight to 115kg, while sacrificing another system and potentially saving 50kg overall for the entire system.

Change happens bottom-up with insurgency. Build traction on culture change with "I did this in an agile way and it worked" rather than theorizing.

Ian Jimenez

VP Engineering, ABL

This is what you want to inspire. Engineers to push back on requirements and kill systems rather than add requirements, more systems, and complexity.

8. Slim down requirements to the bare minimum, then slim them down again

This is the most important thing I’ve learned from SpaceX. One term their leaders use a lot is “future problem.”

If it’s a “future problem,” we don’t discuss it today. Today is about making real progress on the 3-4 things that give us new information. That keeps us in the race, and tomorrow will come.

As an example, let’s take the Starship program when heading into Flight 5. Under the hood, there are probably 2,000+ things engineers want to fix. Major problems on the verge of breaking. This was actually later confirmed during an internal call where it was mentioned that the rocket came within a second of aborting and trying to crash into the ground next to the tower.

The role of a leader is to say what you're not going to do, as well as what you are going to do.

Ian Jimenez

VP Engineering, ABL

Downscoping is the most important thing a leader can do.

Pari Singh

CEO, Flow Engineering

But guess what? Flight 5 ended up being a huge success! The mission was to catch, get data, then move on to the next five problems. If they do that enough times, they’ll fix all 2,000.

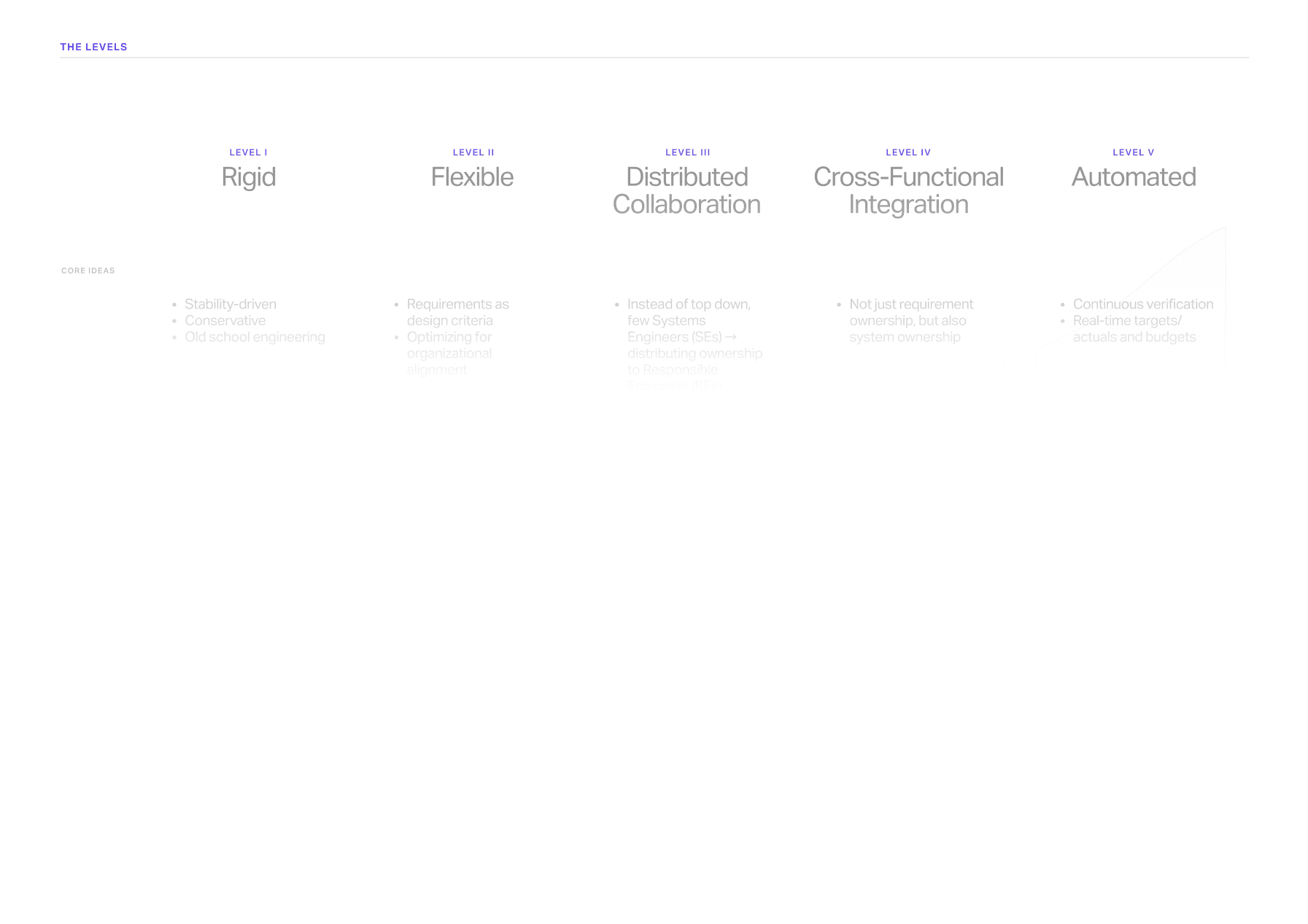

Chapter 3 — Five Levels of Systems Engineering (Maturity Model)

At the turn of the last century, we went from the first sustained flight, to metal aircraft, to rockets, to people on the moon in just six decades. Then, for a period, engineering appeared to flatline. Physical, large-scale engineering faded into the background as software ate the world. New projects now didn't take us a year, it took us a decade. It didn't take hundreds of engineers, it took thousands.

Individual engineers' lives became so much worse—think less inventor and more document administrator. Projects became one long slog of email chains, update meetings, and chasing updates.

Then, in the 2010s, something strange started to happen. Things began to change, and hardware started trying to build the world again. It started small. A few new aero companies here, a handful of space-loving billionaires there, and suddenly a whole new wave of aero, space, and clean & green tech companies emerged.

At Flow, we have worked with hundreds of the fastest-moving engineering teams on the planet. We've observed how these companies are adopting iterative systems engineering to break down complex problems, de-risk faster, and deliver hardware at an unprecedented pace.

From reusable rockets to fusion moonshots to android robots to hypersonic aeroplanes, the future of hardware arrived.

Download the Full Maturity Model (PDF)

A reference guide drawing from real-world patterns and industry best practices. Benchmark your teams, and chart your path to building with speed and flexibility.

Chapter 4 — Requirements: The Modern Approach

How do you manage complexity in a fast-moving engineering organization? For teams like SpaceX, the answer lies in distinguishing between requirements and design criteria. They have even banned the word “requirements” for design teams. Instead, they use the term of “Design Criteria”.This nuanced but critical distinction is the backbone of modern systems engineering, enabling speed, flexibility, and innovation while ensuring mission success.

The Dirty Little Secret of Requirements

Most people don’t know this—early systems engineers were part engineer, part lawyer. They created “techno-legal documents” to manage external contracts. These became requirements.

Requirements were used to manage changes and enforce compliance from contractors. This is where “shall” statements come from and why specific verbiage became essential. Shall statements were legally enforceable agreements in the USA.

This approach influenced early space organizations like NASA, where it started to go wrong. They applied this method, meant for dealing with external parties, to internal ones. It led to the political divides seen in agencies like NASA JPL. Incredible engineers, but an extremely political culture.

Many of NASA’s internal culture issues stem from using requirements incorrectly—as a weapon rather than a tool for collaboration. Engineers hate requirements because they’re used to say, “Don’t think about the wider system, just do what the requirement says.” This created the functional silo.

There’s a reason the SR71 Blackbird was developed without requirements. It needed deep cross-functional collaboration.

The Purpose of Requirements

Modern systems engineering has evolved beyond static, voluminous documents like IBM DOORS or 1,000-page requirement lists. Today’s cross-functional teams benefit from flexible “Design Criteria,” which serve as team-to-team agreements that drive collaboration. These criteria represent internal requirements that are frequently renegotiated and owned by the responsible engineers—those directly accountable for closing them out. By emphasizing a collaborative mindset, “Design Criteria” effectively focus on achieving the overall mission rather than blindly enforcing rigid rules.

However, design must begin somewhere, even if not all details are certain. This creates a paradox: requirements guide design, but design informs requirements. To resolve this, engineers start with their best guess—an assumption—and update it as new information emerges. Marking assumptions clearly and treating them as placeholders encourages teams to routinely check in and make trade-offs based on evolving conditions such as mass, schedule, or other constraints. In doing so, “Design Criteria” become dynamic instruments for moving development forward while ensuring engineers maintain ownership and accountability for each decision.

External requirements from customers, regulators, suppliers, or partners can ideally be approached with the same collaborative spirit. Instead of locking everything down early, teams can engage in open dialogue about trade-offs (e.g., delivering a lighter payload sooner or a heavier payload on schedule). Regulators, too, might be flexible when shown a safe, well-reasoned approach. The goal is to negotiate what’s truly necessary at the top level and keep internal requirements as fluid “desirements” that adapt to real-world project demands.

By placing requirements directly in the hands of responsible engineers and encouraging open negotiation with all stakeholders, teams can respond swiftly to changing conditions and make more informed decisions. This iterative approach not only streamlines development but also ensures that every requirement—whether internal or external—serves the mission effectively.

Centralized vs. Distributed Collaboration Model

Traditional teams have all engineers feeding into Systems Engineering & Project Management. For a change, teams must tell systems engineering, which then propagates it to others.

This model is slow and hinders speed/iteration. Desirements enable direct, cross-functional team feedback. Cross-functional teams should be connected in a flatter, less hierarchical structure.

Successful teams move from the centralized (hub and spoke) model to a distributed (graph) model. This distributes the workload of keeping requirements up-to-date across the team, not just systems engineers.

So what do systems engineers do when responsible engineers own desirements? They become the organizational “glue,” focusing on “real” systems engineering work rather than administrative tasks.

Local vs. Global Optimization—Project Requirements

To achieve a global optimum, every team must not always optimize locally. One team may need to design a worse system to support others. In traditional models, teams often only cared about their part, even if the mission failed.

The priority order should always be Mission, System, then Team. Otherwise, “the tail wags the dog.”

Two steps can help:

Continuous Conversations. Empathy among teams comes from regular interaction. In-person teams often do better because they share context and care about each other.

Project-Level Requirements. Establish requirements beyond mission requirements that outline what everyone works toward.

Reduce Complexity — Kill Systems

Step 1: Make requirements less dumb

Step 2: Kill the part or process step

Step 3: Simplify or optimize the design

Step 4: Accelerate cycle time

Step 5: Automate

— Elon Musk

Merge requirements into higher-level “core” ideas where possible. One hundred well-defined requirements are better than 100,000 minor ones. A few clear requirements are more useful than thousands of tiny ones.

This focus helps responsible engineers step out of the weeds, simplifying the system exponentially and increasing its likelihood of success.

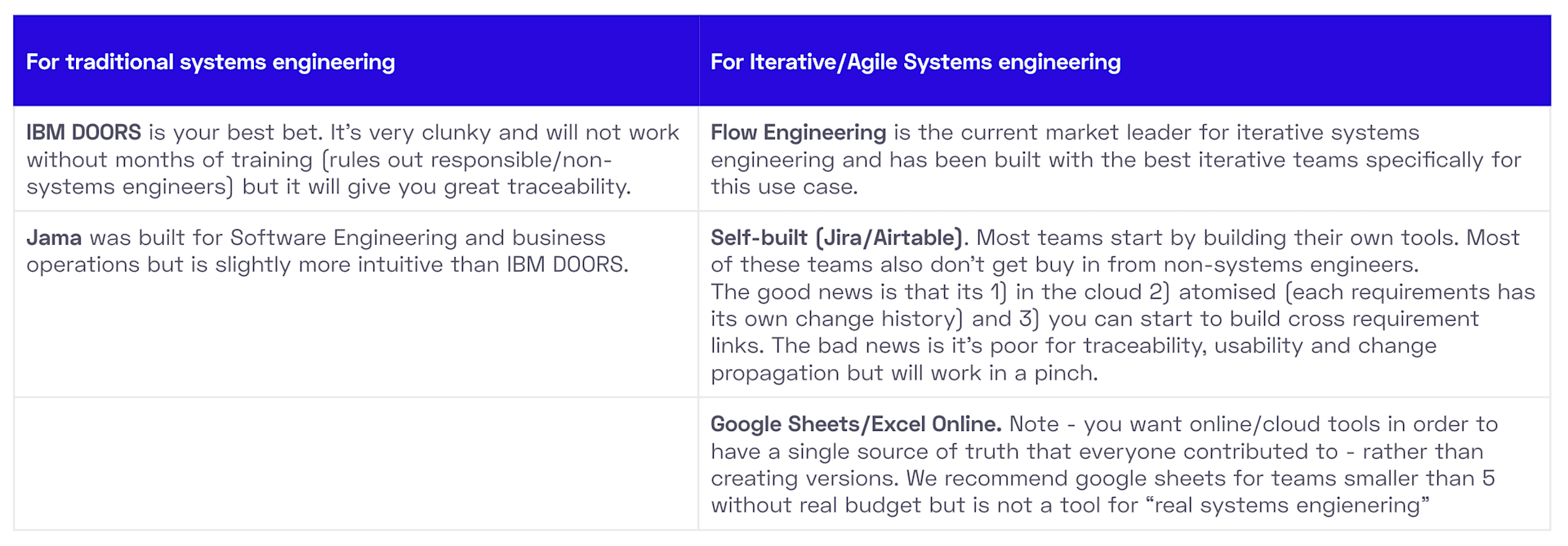

Requirements Management Tool Selection

The first thing to note is people over process over tools. If you hire the right people you will default be successful.

A few key principles:

Accessibility for non-Systems Engineers.

Integration to other tools

Traceability

Automation

In our opinion - there are two different and distinct markets with two leaders.

Continue reading Volume 2